Introducing the ‘bad’ books of the Bible

Inside the so-called Apocrypha—what they are, who they’re for, and why anyone should care today.

Episode 1 of “Bad” Books of the Bible is live! Click below to listen now, or keep reading for some additional background and bonus material.

In or out?

We tend to think of the Bible as a single book. But it’s not. Biblia is Greek for books, plural. The Bible is a collection of books, a library unto itself.

Unsurprisingly, controversy has simmered and even erupted over the centuries about which books belong in that collection and which do not. Some, which were once valued and esteemed, left a bad taste for this or that group—and out they went like last week’s garbage.

It’s a shame, really.

People often call these discarded books Apocrypha, which is pejorative. Apocryphal, after all, is what we label stories we can’t confirm and which might be phony. Still, let’s be honest: We enjoy telling and hearing apocryphal stories, don’t we? They’re just too good to pass up.

Something similar could be said of these books. As we argue in ”Bad” Books of the Bible, our new podcast, these stories are not only too good to pass up, they’re also challenging, useful, and rewarding.

But there’s a problem. There’s also a good chance they’re missing from your Bible.

Missing in action

Grab one off you nightstand or shelf, or wherever, and take a look. If they’re not interspersed throughout the rest of the Old Testament, you can usually spot them right between the Old and New Testaments—which makes sense because these books were written in the window between the Jewish return from exile and the time of Jesus and the apostles.

If they’re missing from your Bible, there’s an equally good chance you don’t have much exposure to these “bad” books. We’re here to remedy that—and have a little fun in the process.

So, what are the ‘bad’ books?

Depending on what books you include, the so-called Apocrypha is longer than the New Testament. Here some key examples from the standard roster:

Tobit

Judith

1–2 Maccabees (and 3, too, depending on who’s counting)

Wisdom of Solomon

Wisdom of Sirach

Baruch

Bonus material for Esther and Daniel (the OT Snyder Cut)

And more.

There’s history, romance, psalmody, prayer—even a detective story. The plan with “Bad” Books of the Bible is to explore these books one by one. And the plan for this newsletter is to shed a little extra light along the way, including bonus articles, art, and other resources.

Yeah, but are they really part of the Bible?

Your answer probably depends on your religious tradition. For Orthodox Christians the answer is yes. For Catholics the answer is also yes, but there’s a little disagreement about which books we’re talking about. For Anglicans the answer is mostly yes; it just depends on what you want to do with them. For evangelicals the answer is no.

As with many controversies, history fails to provide a straightforward answer. Jews wrote these books—but then pretty much abandoned any use of them. There’s evidence of synagogue use of Tobit in the Middle Ages, for instance, but by the middle twentieth century Jewish American novelist Saul Bellow introduces the Book of Tobit like the titular character is a stranger.

The apocryphal books, says Bellow in his collection, Great Jewish Short Stories, are “near-scripture” and he assumes little familiarity among his readers. (1) Jaroslav Pelikan describes them as “post-Scriptural scriptures,” because they were written after the time the Hebrew canon was supposedly closed. (2)

It’s Greek to me

Books that had the best chance of making the cut, as far as Jews were concerned, were those with Hebrew originals, even if their more popular expressions were found in Greek translations. That meant Tobit did have a chance. And rabbis debated the fate of Sirach for a long time before it eventually fell by the wayside.

Except, it didn’t! At least not for Christians.

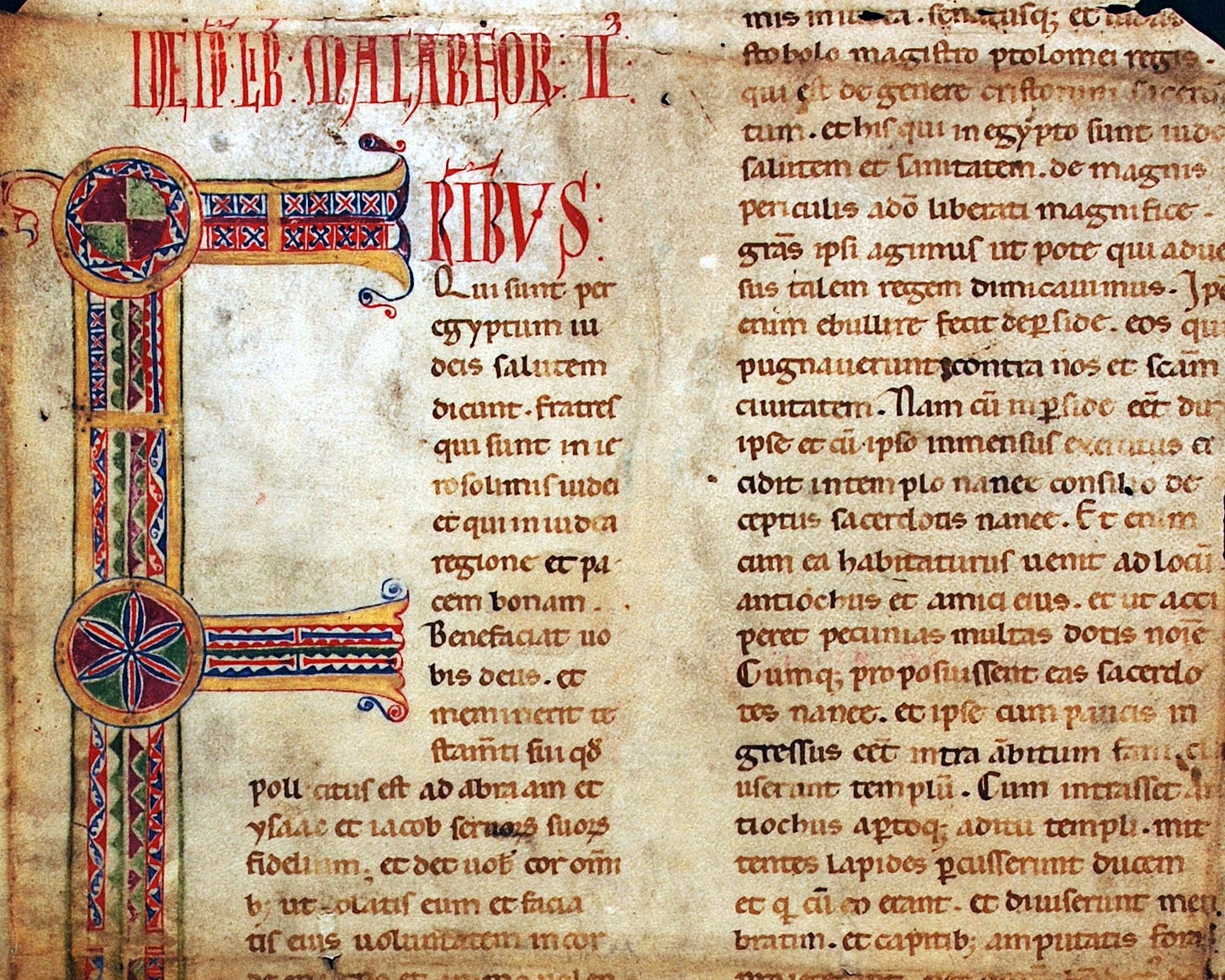

Greek translations of these books could be found in the Septuagint, which started as a Jewish translation of the Torah and other writings and ended up, more or less, as the authoritative Old Testament for Christians. If you see the Old quoted in the New, odds are good it’s from the Greek translation. And all these “bad” books were in Greek!

Christians picked them up and ran with them. Scholars like Timothy Michael Law point to instance after instance of Septuagint formulations affecting later Christian imagination and use. (3) That’s why Orthodox Christians, who never stopped using the Septuagint, basically treat these books as Holy Scripture, whatever anyone else thinks about them.

And, admittedly, the thinking has been mixed.

Differing opinions

Various church fathers had varying opinions of these books. Gregory of Nazianzus warned of “strange books . . . full of interpolated evils” and offered a list of Old and New Testament scriptures—excluding these books from his approved number. (4) Even then, however, he might not have meant these books in particular because he nonetheless quotes from them in his sermons.

Athanasius of Alexandria also considered them noncanonical but actually recommended Christians read them—especially new converts! For Athanasius these books were not scandalous; rather, they had a praiseworthy pedigree and were preparatory for understanding the faith. (See his thirty-ninth Festal Letter, a snatch of which is quoted below.)

Most importantly for their fate in the West, Jerome wasn’t a fan. He favored the Hebrew copies of the scriptures and downplayed the Septuagint, including the Apocrypha. In fact, he seems to have been among the first to use that term to describe them:

Just as there are twenty-two elements [letters], by which we write in Hebrew . . . thus twenty-two scrolls are counted, by which letters and writings a just man is instructed in the doctrine of God, as though in tender infancy and still nursing. . . . [W]hatever is outside of these is set aside among the apocrypha. Therefore, Wisdom, which is commonly ascribed to Solomon, and the book of Jesus son of Sirach, and Judith and Tobias, and The Shepherd are not in the canon. (5)

Despite his reservations, however, Jerome retained and translated these books in his Vulgate Bible. (“I implore you, reader, that you might not consider my work a rebuke of the ancients,” he said.) And Catholics still use them today.

I (Joel) grew up assuming they were essentially “Catholic” books. We suspect that’s how many Protestant and evangelical Bible readers think of them.

Interestingly, the Anglican Church still approves of these books and prescribes their formal use. But most of the Reformational churches eventually let these books slip out of circulation at one point or another—sometimes for simple publishing reasons (e.g., they cost extra money to print), other times for strenuously argued theological reasons (e.g., belief they contain false doctrines).

So now what?

Here’s an idea: What if we put all these arguments aside and just read these books for ourselves?

We’re convinced that readers from any Christian tradition will find these books interesting and valuable to one degree or another—same with Jewish readers. That is, after all, why Jews wrote these books in the first place and why Saul Bellow included Tobit in his collection of Jewish short stories.

And that’s what we’re doing with “Bad” Books of the Bible. We’re covering the so-called Apocrypha one book at a time. Conversations will include the nitty gritty of the stories themselves, plus ancillary questions that help with context, interpretation, ongoing relevance, and more.

To serve that end, we’ve included some additional quotes and a bonus article below to help round out the newsletter this week.

Useful quotes

There are other books . . . which have not been canonized, but have been appointed by the ancestors to be read to those who newly join us and want to be instructed in the word of piety: the Wisdom of Solomon, the Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, Tobit, the book called Teaching of the Apostles, and the Shepherd.

—St. Athanasius of Alexandria (6)

However strongly evangelicals, as part of the larger Protestant tradition, reject the Apocrypha as Scripture, they can no more dismiss this corpus from all consideration than they can write off the world and culture into which the Christ was born, and in which the New Testament was written.

—D. A. Carson (7)

A major concern addressed in by many of these texts involves how Jews are to respond to the challenges of perservering as a minority culture in a Greek world while also taking advantage of the good things that Greek world offers. It is perhaps this aspect of the Apocrypha that most draws me to these texts, since similar questions continue to face the community of disciples. What challenges threaten the commitment and the faithful practice of the contemporary people of God? How can we discover and persevere in a faithful response to God in our world?

—David A. deSilva (8)

Bonus article

One helpful summary of the historical setting of the “bad” books can be found on DesiringGod.org by Westminster Theological Seminary Professor David Briones: “What Is the Apocrypha? Listening to Four Centuries of Silence.”

His sections on the Hellenization crisis and the Maccabean revolt provide valuable context these books, while the whole piece establishes the value of reading the so-called Apocrypha alongside the rest of the Bible. It’s especially useful if you come from a tradition that might otherwise look down on these books.

Where you come in

If this subject intrigues you, we’re delighted. In fact, we’re doing this show for you and people of like interests and similar. Let’s connect and help others connect, too.

For starters, please use the comment feature below and let us know what you think about the show, the subject, what we get right, what we get wrong, and all the rest.

Here’s a question to start us off: What’s your experience so far with these “bad” books of the Bible?

Next, please share this newsletter and help us get the word out so we can reach the Apocrypha fans, Apocrypha-curious, and those who’d rather read Leviticus but who might be persuaded if they just knew what was inside.

If you haven’t jumped over to Ancient Faith to listen to episode 1, please do so now. The show is live now and itching for a listen.

And, finally, join us next week as we wade into the Book of Tobit!

Saul Bellow, Great Jewish Short Stories (Dell, 1963), 17.

Jaroslav Pelikan, Whose Bible Is It? (Penguin, 2005), 70.

Timothy Michael Law, When God Spoke Greek (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Gregory of Nazianzus, Poems on Scripture, translated by Brian Dunkle (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2012), 37.

“Jerome’s ‘Helmeted Introduction’ to Kings,” translated by Kevin P. Edgecomb, Biblicalia, July 27, 2006. Emphasis added.

As translated by David Brakke, “A New Fragment of Athanasius’s 39th Festal Letter: Heresy, Apocrypha, and the Canon,” Harvard Theological Review 103:1 (2010).

D. A. Carson, “The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: An Evangelical View,” in John R. Kohlenberger, ed., The Parallel Apocrypha (Oxford University Press, 1997).

David A. deSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha (Baker Academic, 2018), 2–3.